.jpg) |

| The Lost Child, PS Vita/PS4/Nintendo Switch (2017) |

The Lost Child was released to the world on August 24th, 2017. "Something wicked lurks behind the facade of the modern world. Hayato Ibuki, occult journalist, is on the case!" reads a series of captions in the trailer for the English release. "This looks cool, I got Shinigami Tensei wibes from this" reads a comment on that same video. Absolutely.

A budget dungeon-crawler developed according to the specifications of the PlayStation Vita and released as the window of viability for games of this lineage had closed, The Lost Child follows on the genealogy of such works that have steadily emerged since the Japanese 'occult boom' some six decades prior, and signifies an especially diluted form of the urban-occult fantasy exemplified by the Megami Tensei series. Actually playing this game is like being whipped in the face with banality, but there is a strange specificity of context, with little to no documentation in English, that demands closer examination.

BACKGROUND: THE SAWAKI TAKEYASU UNIVERSE

.jpg) |

| El Shaddai (Steam, 2021; orig. 2011) |

We should first consider The Lost Child in relation to its predecessor, the 2011 action-platformer El Shaddai: Ascension of the Metatron, and the circumstances of its release. Developed under the name Angelic and spearheaded by Sawaki Takeyasu, a character designer associated with the defunct studio Clover (Okami) and their successor Platinum Games (Infinite Space), there was much in El Shaddai to suggest a passion project fated for minor cult status. While possessing tonal and narrative qualities that would require an article of equal breadth to discuss adequately, its legacy and reception are tied (not unjustly) to an aesthetic virtuosity. El Shaddai is gorgeous- as art object, the sort that critics might breathlessly describe as "kaleidoscopic"- and this splendor was wedded to a rarely evoked branch of Gnostic apocrypha, the details of which derive from the first section of Enoch. Marketing for the game emphasized these points, often calling to mind Takeyasu's work on Okami and suggesting a common ancestry between the two as mythological works united by a singular aesthetic vision.

Those superlative qualities, the quiet intelligence and thematic reach, are not present in The Lost Child. This is a fact that evaded few observers even prior to the game's release, a discourse marked by wide recognition of an obvious, derivative quality. Reactions to the content proper were so muted that attentions were soon monopolized by the peculiar presence of artist Kazuma Kaneko in a roundtable interview published in 4gamer magazine, breaking a years-long silence to discuss a game with which he was unaffiliated but which was obviously cast in an imitative mold of the Megami Tensei series; five years have passed since its publication and yet this interview remains the only substantive public appearance by Kaneko in the last decade.

|

| (From left to right) Zin Hasegawa, Sawaki Takeyasu, and Kazuma Kaneko |

Aside from Kaneko's contributions, the interview helps us to anchor our understanding of

The Lost Child and its place in Takeyasu's oeuvre by introducing the conceit of the "Mythology Directory". As the name suggests, Takeyasu's interest in myth did not expire with the middling sales reception of

El Shaddai- though industry credits during this period include only a few contract positions as designer, there exists a concurrent, independent creative practice spanning prose works, picture books, and art exhibitions; myth is everywhere the dominant theme, whether an elaboration of the setting introduced in

El Shaddai or in adapting material from Eastern religion. The latter includes

Gaki: A Girl and Monster's Night Parade, a lavishly illustrated picture book of Japanese folklore, while the former consists of various novellas released under the

SawakiGraph banner, a series of novel adaptations, and a three-volume manga prequel to the original release.

|

| Painting displayed at Hidari Zingaro Gallery |

This universe is the answer to an obsessive impulse. Works expounding upon the setting and characters introduced in El Shaddai succeed the obscurant qualities of the original narrative, which dealt in a continued revelation of absence; many of the objects of Enoch's pursuit perish prior to his arrival, settings are ethereal non-places, and history is revealed with artful simplicity. Time passing lightly by, into pure texture. El Shaddai is concerned not so much with faithfully reproducing the textual details, but the ineffable feeling of myth.

This dream-quality would seem less likely to withstand the tremendous amounts of text and explication implied by these elaborations in prose, but Takeyasu allays the issue by playing only loosely with notions of canon. This is enforced by the presence of Lucifiel, who moves freely across time, overwriting events and permitting various degrees of narrative focalization. The heavenly host is expanded with the likes of Jophiel, Remiel, and Zerachiel in

Heavenly 7, while the superbly titled

Gideon: The man whom God disliked conjures the character of Gilgamesh, a complement to competing near-east figures Ishtar and Inanna in

El Shaddai.

.jpg) |

| Various novellas authored by Takeyasu |

The universe of the Mythology Directory is further divided between two visions: Ceta and Ryuta. It would require a more comprehensive understanding of those untranslated works to establish a criterion of distinctions between the two, but suffice to say that these represent separate worlds with shared themes and unique interpretations of many of the same figures and settings: El Shaddai takes place in the world of Ceta, The Lost Child in that of Ryuta. Concepts and designs introduced in one recur in the other; the unnamed angel whom Michael consults over the course of The Lost Child is Raziel from Heavenly 7, for instance. This partition exists to brace the audience for the tonal and aesthetic chasm between the two titles, and Takeyasu forsees tension: "Perhaps the people who already know my ‘Mythology Directory’ will react naturally to The Lost Child. If they only know El-Shaddai, they’ll probably feel a little uncomfortable at first."

All wildly obfuscated to a western audience- in Japan the special edition of

The Lost Child was packaged with a primer on the Mythology Directory, a text that would have been incomprehensible overseas as a referant to countless untranslated novellas. Regardless, even a cursory scroll through

an author page offers an idea as to the depth of passion invested in this project. Such obvious devotion is unusual among industry professionals; designers in Japanese comics and game spaces will often admit to being funneled into these roles by a lack of other profitable skills or interests and would otherwise not maintain such an expansive creative practice but for financial neccessity- prolonged exposure to the notoriously cruel labor conditions of these industries would staunch even the hardiest creative appetite, in any case. Even where this is not the case, creators in the game-making space are rarely in possession of their intellectual properties; Takeyasu notably acquired the rights to

El Shaddai from Ignition Entertainment and founded the independent studio Crim in 2013.

.jpg) |

| Yoshitaka Amano's influence evident in AMON: The Code of DEVIL |

So, The Lost Child is best understood not as a direct sequel to 2011's El Shaddai, but as an extension of the multimedia mythology conceived by Takeyasu in the years since, its second realization in the medium, and the only work of its kind to receive an official English release. I don't mean to imply, however, that profundity follows from this convolution- as already suggested, The Lost Child is insipid. The interview above states that Kadokawa approached Takeyasu with a proposal for a dungeon-crawler modeled on the basically contemptible Demon Gaze. Even were it not to share a foundation with purposefully trite otaku ephemera, the impetus was still supplied from without rather than from within. This is not to say that Takeyasu's passion would instantly translate to something of value- by merely noting the sheer volume of his output one could imagine at least a portion is superfluous. But were it the product of a more personal investment, it might rise to the level of idiosyncrasy- there would be something to note in it. As is, it feels torturous to designate The Lost Child with a catalogue of negative descriptors. The phrase that comes to mind is "not deserving of serious contemplation."

THE LOST CHILD

|

| Michael and Shu converse in The Lost Child |

In contemplating, seriously, the special qualities of The Lost Child, some degree of foreknowledge is essential. I do not expect that many reading this have played the game to completion. Plot synopses are scarce, so one has been provided below:

Hayato Ibuki is a contributor at the Shibuya-based occult editorial LOST. One day he is entrusted by a mysterious woman with a mystical artifact known as the Gangour, a weapon capable of capturing demons and spirits ('Astrals'). Soon after, Lua, a woman who identifies herself as an angel, declares Hayato the Chosen One and enlists his aid in a battle against the Lovecraftian council, a group of elder gods who are attempting to channel the power of certain sacred obelisks to conquer the living world- a trio of fallen angels interfere with the protagonists to unspecified ends. In the latter half of the game, it is revealed that the obelisks, which Lua and Hayato have gone about destroying in their conflict with Cthulhu etc., were central to the preservation of the mortal world, and the fallen angels were merely attempting to allay calamity sent by God. At this point the Egyptian solar deity Ra emerges with his followers to declare his intention to destroy humanity and start anew. Hayato is revealed to be a descendant of the first race of humans, distinguished by their light blue hair. Lua and Hayato confront Ra to prevent the destruction of the mortal world.

(Get it, Hayato is the 'Lost Child' because he is descended from a lost ansecstral race. Also the fucking magazine is called LOST. )

|

| Pictured: Cthulhu (Cthulhu) |

This is a loose sketch of the overall plot and excludes much of the supporting cast and their attendant motivations, but these are not so pressing as to demand elaboration. The points described above are delivered in a perfunctory way, tiredly striking the dramatic beats expected of the genre: the chosen one of a sacred lineage, the feminine otherworld guide, the capricious deity (represented in Ra's disguise as a human child), even the destruction of those points of power which is revealed to have catastrophic consequences. Thematic material from El Shaddai is also regurgitated, evident in the sympathetic portrayal of the fallen angels and their overweening passion for humanity. But if there is some unique or worthwhile meaning within the carelessly recycled semiotics of The Lost Child, then I admit myself incapable of extracting it.

A special emphasis has been placed upon the relation between El Shaddai and The Lost Child, as this is one of only two compelling points of interest available to us. The other, then, would be the unveiled influence of the Megami Tensei series, endorsed by director Zin Hasegawa: "... Still, if the setting is current day Japan and you add demons and angels, then yes, it’s basically Megaten, just like Kaneko said." This unity of modernity and myth is not so unusual today as it may have been in 1992, but Megami Tensei remains the popular touchstone. The Lost Child gestures towards a greater specificity of setting by focusing on Shibuya and its attendant locales, but the effect is much the same as any other game, and much diminished by the limits of the strictly visual novel presentation. But absent the transformative qualities of the apocalyptic arenas of Shin Megami Tensei, a closer analogy would be something like the Devil Summoner series, given the narrative framing of an investigative specialist navigating the boundaries between sacred and profane within a relatively unspoilt modern setting.

.jpg) |

| (Left) Gangour, (Right) GUMP |

Elements of the series have filtered into the mechanical and visual workings of The Lost Child. The dungeon-crawling and map design owe more to Demon Gaze than anything, but even minor peculiarities in party composition hail back to Megami Tensei: one male protagonist for physical attacks and party administration, one female protagonist with access to a variety of magic (and like the heroine of Shin Megami Tensei, Lua specializes in healing and lightning spells), and a host of creatures recruited during battle. The tool set to these purposes, the Gangour, seems to derive from the GUMP concept utilized in Soul Hackers, but unmoored from the convergence of technology and the occult which was the central thematic concern of that game.

This is emblematic of an issue that runs through many would-be imitators across the genre: not only are elements from earlier titles recast heedless of their thematic import, but there surfaces a myopia of influences. In simple terms, Shin Megami Tensei (1992) was inspired by Wizardry, Devilman, Teito Monogatari, western science-fiction, horror cinema, eastern religion etc., whereas The Lost Child was inspired by Shin Megami Tensei. This is reductive, but it points to the incestuous tendency of popular works to look no further than their own medium or genre to establish an identity- by a sequence of imitation they become the object that signifies only itself, unable to point towards a coherent reality (external or internal), an invitation to escapism.

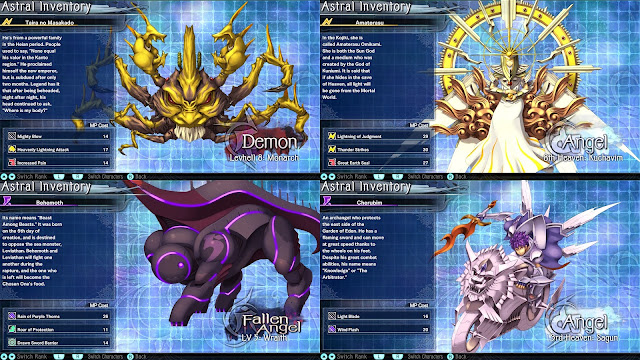

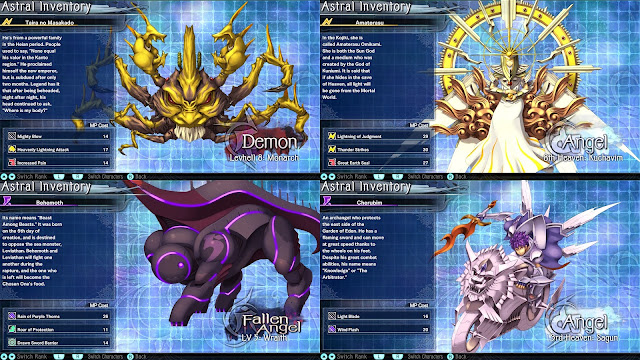

.jpg) |

| (Clockwise from upper-left) Masakado, Amaterasu, Behemoth, Cherubim |

This derivative quality is present at the level of aesthetics, but certain elements assert themselves as distinct from the criteria established by El Shaddai and Megami Tensei. Most striking is a lack of unity between art assets, a dissonance peculiar to the budget dungeon-crawler, wherein design obligations are often shared between multiple artists (see: Unchained Blades, Eliminage etc.). The division of labor is as follows: character designs fall under the purview of animator Naruyuki Takahashi, who also interprets a small number of existing Takeyasu designs originating from previous works. Takeyasu is responsible for the protagonists and the four central figures of the Lovecraftian council, while designer Kentaro Maruta illustrates the many 'Astrals' that populate the world of The Lost Child. (A gallery containing roughly 95% of the bestiary is available here, not including a majority of the second and third form transformations available to each creature.) These are divided into three classes, each equipped with an aesthetic and mythological motif:

- Demons are organic creatures with a loose design schema relative to the other two categories. The standard menagerie of Greek and Lovecraftian monsters are their chief representatives.

- Angels are humanoid figures decorated in sleek chrome and steel. Their numbers are divided between their namesake and beneficient figures from myriad pantheons (Lakshmi, Hanuman etc.).

- Fallen Angels are robotic figures, nearly monochromatic but with forms described by lines of contrasting color. They include actual fallen angels, tricksters, and deities of ambivalent moral character from across the religious spectrum.

According to the largely unexplored ontology of The Lost Child, all religious icons are interpreted through this Abrahamic trichotomy. Cait Sith is literally an angel fallen from heaven, and Amaterasu fights to preserve the order of the one God. But The Lost Child is disinterested in exploring any implications that might arise under this framing. Such elements as the amity between the Egyptian and Abrahamic pantheons, their seeming coequal status, are left uncommented upon. The narrative, almost audaciously, offers nothing. If the prevailing tendency in other works of this genre is to overexplain, to be so eagerly lost in explicating the diarrhea of their own proprietary mythologies that no themes are reinforced, no images introduced, only pure information generated to be later collected into bullet-points on a TV Tropes page, then The Lost Child occupies an opposite pole- unwilling to recognize that the world it asks the player to inhabit could contain greater interest than whatever rises to the surface. Things feel rudderless.

|

| (Above) Concept designs, (Below) Final art |

Turning our attention at last to Takeyasu's contributions, his illustrations for The Lost Child emerge somewhere between the delicate, whispy forms and fashionista proportions of El Shaddai and the more unadorned digital anime rendering of Infinite Space. A shift in style occurred between the earliest concepts for "The Lost Children" and their final incarnations, illustrated above. Takeyasu seems to have constrained the idiosyncrasies of his usual draughtsmanship in favor of a more saturated palette, larger eyes, more ordinary proportions, and some big honking titties. Koji Igarashi's comments on the shifting art direction of the Castelvania series on reaching the DS era enter the mind: "And that is the anime style chosen in Dawn of Sorrow... the rationale there was that people who were gaming on the DS continue to get younger and younger versus previous handhelds. And if you, with the franchise, don't continue to try and get new fans and new customers, then you just end up with older and older gamers that sometimes stop gaming or peter off. So that was pretty much us trying to appeal to new, younger users, to try to get them interested in that series."

As development was initiated by Kadokawa Games, it is tempting to imagine the rift between concept and finalized asset as emerging from the mandates of a company chiefly occupied in the development of vapid anime dungeon crawlers. As can be discerned from these concepts, Hayato has undergone the least severe transformation; his appearance never entered consideration as a potential asset in marketing the game as masturbatory fodder for an audience of majority male adolescents. This same tendency is present as comical dimorphism in the transfigured forms of the fallen angels designed by Naruyuki Takahashi (see below).

.jpg) |

| (Clockwise from upper-left) Jeqon, Balucia, Samael, Mastema |

So, certain insight on the tonal and artistic aspirations of The Lost Child can be gleaned from these qualities of design, narrative, and influence. With sights thusly set it isn't difficult to imagine how the final product might have coalesced around inert mediocrity. But my affection for El Shaddai demands that I note that The Lost Child is not totally bereft of endearing qualities. The systems concerned in maintaining a party of Astrals are as engaging here as in works of analogous scope, and this take on Shin Megami Tensei's Cathedral Master is very charming.

I find it difficult to root against Takeyasu, even as my attribution of the many failings noted above to the bloodless stewardship of Kadokawa may prove unfounded. This article was published on the 11th anniversary of El Shaddai's release, and a port for the Nintendo Switch is currently being developed by Crim. If another return is at hand, then I can only hope that a greater degree of independence might allow Takeyasu's clearly abundant ambitions a more fruitful realization in the medium.

- Special thanks to Dijeh for translating the 4gamer interview that became the constant source for this article!

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

I have had some interest in the artist behind El Shaddai and, the as you stated, insipid, Lost Child. Now that I actually know where to look, I may look into more of his art. The 'Gaki' art book is intruiging.

ReplyDeleteGood call, and yes, something like Gaki seems close to an ideal receptable for Takeyasu's talents. Definitely worth looking into!

Delete